Recently, my residency program has been working on how we help patients with pain. Honestly, some of this comes from the great frustration the doctors and staff at our three clinics feel with "pain patients." It feels like patients with chronic pain take up a lot of our time and energy, and we end up not helping them very much--they still have pain. Stuck in our doctor brains is the notion that if something is wrong, we should be able to fix it, or at least help patients fix it. So when things don't get better--the pain is the same or worse--over months of treatment, we get frustrated, and so do our patients.

Recently, my residency program has been working on how we help patients with pain. Honestly, some of this comes from the great frustration the doctors and staff at our three clinics feel with "pain patients." It feels like patients with chronic pain take up a lot of our time and energy, and we end up not helping them very much--they still have pain. Stuck in our doctor brains is the notion that if something is wrong, we should be able to fix it, or at least help patients fix it. So when things don't get better--the pain is the same or worse--over months of treatment, we get frustrated, and so do our patients.One of the most difficult issues revolves around pain medications, specifically narcotics. Treatment of chronic pain with opioids (commonly vicodin, percocet, oxycodone, and methadone in our clinics) has a long history, and opinion about its value and safety seems to swing like a pendulum. In primary care settings, the pendulum has swung into the "avoid narcotics" zone over the last several years. There is a lot of well-founded concern for the long-term safety of narcotics, and for the harm we do to patients by creating dependence on these medications. But that's not what really makes us uncomfortable.

It's a trust thing. Misuse of narcotics--overuse, diversion--is a reality, and doctors are justifiably nervous about the possibility that the potent medications we prescribe might be used to feed addiction or for monetary gain. There's good evidence that this happens, even among patients we believe to be using narcotics appropriately. We can't be sure, and we're not comfortable with a sham therapeutic relationship.

Unfortunately, that anxiety about trust sets up a difficult relationship with patients when they come to us with pain. When I hear a patient report low-back pain, my differential diagnosis always includes inappropriate drug-seeking behavior. There is no other complaint that sets off these kinds of alarms. I find that when this suspicion come up, I might test a patient with a few non-narcotic suggestions, like physical therapy, but these maneuvers only contribute to the discomfort and don't clarify anything. Worse, failure to embrace physical therapy as the best idea ever and suggest, perhaps, a short course of vicodin ("I had some left from a procedure and they seemed to help") puts the patient at risk of being branded as a drug seeker--the pseudo-addict.

All of this has been stuck in my sleepy head recently as I've done this narco-dance with a few new patients and worried a lot about how to wean the few patients of mine who take opiates chronically. The residency pain task force is doing it's thing, and will certainly produce some helpful resources for my patients, but I'm not good at waiting, and the folks I care for have pain now.

A couple of weeks ago I put together a five page "Menu of Treatments for Low-Back Pain" for one of my patients. I had hoped to use some chronic disease management techniques to create a plan with her that would be as transparent as possible. I created the menu from the collected works of the Cochrane Back Group and offered it to her as a way to start us both thinking about how to help her to a tolerable level of pain. The menu concept is popular in managing chronic diseases like diabetes and hypertension that require patients to change behaviors. It gives people options and lets them choose what they think they can do. It is important to build the menu around goals--another chronic care pillar--and so we spent some time discussing what she hoped to accomplish regarding her pain. I thought it went well.

A couple of weeks ago I put together a five page "Menu of Treatments for Low-Back Pain" for one of my patients. I had hoped to use some chronic disease management techniques to create a plan with her that would be as transparent as possible. I created the menu from the collected works of the Cochrane Back Group and offered it to her as a way to start us both thinking about how to help her to a tolerable level of pain. The menu concept is popular in managing chronic diseases like diabetes and hypertension that require patients to change behaviors. It gives people options and lets them choose what they think they can do. It is important to build the menu around goals--another chronic care pillar--and so we spent some time discussing what she hoped to accomplish regarding her pain. I thought it went well.Mind you, in several visits we haven't touched on her hypertension, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia. And I haven't gotten close to talking about preventive care: pap smears, osteoporosis, etc. Missing these things is another hazard of chronic pain.

Okay, so I started this not to whine but to describe a chain of events and some hopeful developments. The back pain menu was a nice little organizing moment for me. There are heaps of options for patients with pain. For any given intervention, the data might not be thrillingly positive, but most of them work for somebody, and in combination, I have to believe that we can find a way to decrease pain.

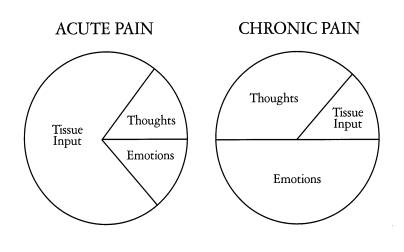

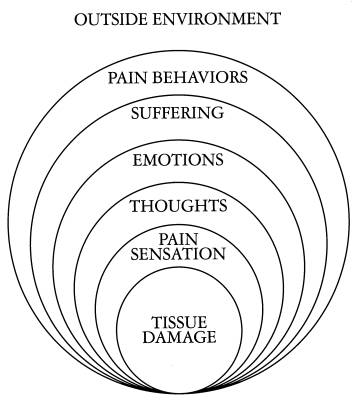

We've also got resources in our own clinics. Like chronic disease management techniques, cognitive behavioral therapy techniques have a place in the management of chronic pain: one's process of thinking-feeling-behaving is vital to one's experience of pain.

As an exercise in organizing these ideas into a practical approach, I'm working on a web-based collection of resources. The Pain Page will catalog evidence-based interventions for pain, local resources, patient perspectives on living with pain, media coverage of related issues, and how our work as physicians and patients relates to regulatory bodies.

I hope this will help my colleagues, patients, and me build together a transparent and effective structure for collaborating on a problem we all would like to handle better.