Sunday, March 18, 2007

Friday, March 16, 2007

Movin' On Up

Algorithmanic episodes

Jerome Groopman has been all over NPR the last few days giving interviews about his new book, How Doctors Think. This morning he landed a seven-minute session on Morning Edition, and recently spoke at length with Terry Gross on Fresh Air. The book sounds like a well-constructed inquiry into the algorithmic processes of doctor think. How do physicians make sense of patients' stories and arrive at a diagnosis?

Jerome Groopman has been all over NPR the last few days giving interviews about his new book, How Doctors Think. This morning he landed a seven-minute session on Morning Edition, and recently spoke at length with Terry Gross on Fresh Air. The book sounds like a well-constructed inquiry into the algorithmic processes of doctor think. How do physicians make sense of patients' stories and arrive at a diagnosis?Or a mis-diagnosis. Groopman discusses the experiences of physicians and patients--even his own experience as a patient, to point out where doctor think goes wrong. The diagnostic process, relies on information from the patient about symptoms, personal and family history, risk factors. Doctors then collect relevant "objective" data (physical exam, labs, studies), and assemble a list, or differential diagnosis we think might explain what the patient is experiencing. Ideally, it's an exhaustive list, and we narrow it with directed studies to rule things in or rule them out. We work hard at it, but for various reasons we don't always get it right, and the consequences can be severe. Dr. Groopman explains to Steve Inskeep on Morning Edition:

An anchoring mistake? Sounds like what my people call early closure, a very common"Usually doctors are right, but conservatively about 15 percent of all people are misdiagnosed. Some experts think it's as high as 20 to 25 percent. And in half of those cases, there is serious injury or even death to the patient."

Why do you think that doctors would be wrong that often?

Well, you know, it's very hard to be a doctor. We're working under tremendous time pressure, especially in the current medical system. But the reasons we are wrong are not related to technical mistakes, like someone putting the wrong name on an X-ray or mixing up a blood specimen in the lab. Nor is it really ignorance about what the actual disease is. We make misdiagnoses because we make errors in thinking.

We use shortcuts. Most doctors, within the first 18 seconds of seeing a patient, will interrupt him telling his story and also generate an idea in his mind [of] what's wrong. And too often, we make what's called an anchoring mistake — we fix on that snap judgment.

problem. Making big differentials is hard, and many things influence how quickly we decide we know the diagnosis. Often, it just seems to fit...mostly...more than other stuff. But is our list comprehensive? Did we consider only common diagnoses? Is is time to trot out the rare, eponymous syndromes we memorized in med school but have never seen? Deciding early to attach a diagnosis to a symptom feels good, especially when there are other patients with symptoms waiting to be seen.

problem. Making big differentials is hard, and many things influence how quickly we decide we know the diagnosis. Often, it just seems to fit...mostly...more than other stuff. But is our list comprehensive? Did we consider only common diagnoses? Is is time to trot out the rare, eponymous syndromes we memorized in med school but have never seen? Deciding early to attach a diagnosis to a symptom feels good, especially when there are other patients with symptoms waiting to be seen.There's something about categorization that appeals to me. Calling something anchoring mistake, when you could just as easily call it laziness, gives me a kind of hope. If I miss a diagnosis and because I'm lazy and the remedy is to "try harder," well, I'm screwed. The problem and the solution are both pretty vague, and my fear around messing up again takes over. Fear motivates, for sure, but I would argue the outcomes aren't so great.

If I can categorize my apparent laziness with nifty terms like anchoring mistake (in which I make a snap judgement) or representativeness error (wherein I tell myself that common things occur commonly), my type-A doctor mind has something productive and familiar to do: memorize a list. In this case, knowing the ways my thinking might not serve me well helps me see potential pitfalls in diagnosing and treating--also known as helping--patients.

I haven't read the book yet, but I will. I did, however read Dr. Groopman's article from January 29, 2007 in the New Yorker. The writing is excellent and the examples compelling. If the book is anything like the article, I'll be reading all weekend.

Match Day

"The Match" -- a high-anxiety cap to the end of a grueling four-year medical education -- will determine their professional futures, not just where they will live for the next three to seven years, but what specialty they will pursue.Well, that all sounds quite difficult, doesn't it? True, medical training isn't easy, but it's not Darfur. There's a language tossed around in the press that creates this mystique of systematic torture by drill-sergeant faculty.

There's a buzz going on, but the excitement has the tamped-down quality of people who have learned to manage anxiety to survive the rigors of clinical rotations, being called out for not knowing answers during rounds and monster exams.

There is recognition, too, that as hard as medical school was, residencies, renowned for their brutal on-call schedules, can be even harder.

The UWSOM event is quite informal: lots of milling about, tamping down anxiety and eating dry pastries until the envelopes are distributed. You can open your envelope when you want and with whom you want. Some schools parade students in front of a crowd to read their "fate" for everyone. Check out this video from yesterday's University of Cincinnati Match Day event.

I would rather die than participate in that. Sorry, Shannah.

On the residency end, we go about our business on the morning of The Match and wait for a mid-morning page with the list. I got the page as I was strolling home from my massage through a sunny Seattle park. Quite a different scene than in Cincinnati or even at here at UW. I was thrilled with how we matched overall and especially at my beloved Downtown Public Health clinic.

Back to my brutal schedule--last legitimate day of vacation.

Thursday, March 15, 2007

What the fe-mail-man brought

March in Seattle

Out walking this morning I tried to capture these brilliant yellow blooms with my low-res camera phone. Not too impressive, but also gives me an opportunity to figure out how to post directly from my phone.

More vacation

Yesterday there were a couple of things on the list that I felt I had to do. We got rid of Brooke's desk the other day--gave it to Hilary and Dan for their new house--to free some space for a crib, glider, and changing table Brooke picked up on craigslist. Those things go into the current guestroom, soon to be Elliott's room. The desk is gone, and all the stuff that had been in the desk was on the floor, waiting for me to sort through it. What a lot of junk: about 75% of it went straight out the door, either to the garbage or to Goodwill. There is still some stuff there that I couldn't part with (but should). I created a defer decision pile and made some lame excuse to Brooke for why I couldn't deal with it that moment. She didn't buy it, but she didn't call me on it, either. So there it sits. Overall, I did not enjoy that chore.

Next on the list was to return a bed to Ikea. Brand new and yet-unassembled (but out of the box), we slogged it down to Southcenter (big box retail hell) to get it out of Elliott's room. That was the second unused new bed we unloaded this week. Ikea gave us store credit, since we were beyond the return period and didn't have a receipt. We walked around the store for a while and found some more crap to bring home to replace the stuff we spent the morning purging. New crap, though; the other stuff was old crap.

On the way home the first thing we did was get lost. Happens every time we go to Big Box Hell. After a slow tour of the Valley Medical Center parking lot, we inched onto the freeway and

eventually onto the I-405 HOV lane, which moved at about 60mph while the other three lanes literally sat still. Traffic was miserable all over due to accidents and a big police foo-faa over a stolen car.

eventually onto the I-405 HOV lane, which moved at about 60mph while the other three lanes literally sat still. Traffic was miserable all over due to accidents and a big police foo-faa over a stolen car.I hate car life. I would prefer to walk or bike or bus or run everywhere I need to go. But...but...you know I'd like to say now "that's just not practical." But...it IS practical. As Bus Chick points out every day, we've got great public transit. I could easily take Zoë around town on my bike, and the trip from here to daycare and work is all on trails or wide, dedicated bike lanes. And I've demonstrated to myself that running is feasible, having commuted that way nearly all of last year. But then I got a car. Terrible idea! Immediately I started driving, taking advantage of the free parking I have at work and the ease of just getting in and going. I've paid the price with ten pounds gained and physical fitness lost. If I can park a car at work, I can also park a jogging stroller.

Just takes a little planning, which will be easier when I'm not so sleepy all the time. Any day now, I'm sure Elliott will just sleep right through the night. Any day.

Tuesday, March 13, 2007

Vacation

I'm off work this week. It's good. We thought about going away for a few days, renting a cottage on Whidbey Island or Hood Canal. That would be good fun, if it weren't for Zoë and Elliott and their dueling sleep schedules...well, their awake schedules, I should say. It's bloody exhausting. Weekends turn out to be pretty hard, and three days in a cottage, even in a lovely setting and even with a hot tub, would have been less like a vacation than like work. The alternative was to stay in Seattle, send Zoë off to day care in the morning, and enjoy life with one very portable infant. We can take naps, write, go for walks, get massages, all thanks to the happy two-parent-to-one-child ratio we used to think was so hard. Yesterday we called Sam to babysit for the afternoon, then headed out for lunch at High Spot and a walk. No nap.

I'm off work this week. It's good. We thought about going away for a few days, renting a cottage on Whidbey Island or Hood Canal. That would be good fun, if it weren't for Zoë and Elliott and their dueling sleep schedules...well, their awake schedules, I should say. It's bloody exhausting. Weekends turn out to be pretty hard, and three days in a cottage, even in a lovely setting and even with a hot tub, would have been less like a vacation than like work. The alternative was to stay in Seattle, send Zoë off to day care in the morning, and enjoy life with one very portable infant. We can take naps, write, go for walks, get massages, all thanks to the happy two-parent-to-one-child ratio we used to think was so hard. Yesterday we called Sam to babysit for the afternoon, then headed out for lunch at High Spot and a walk. No nap.Last night, we gave Elliott a bath, which I videotaped and and

might post if Brooke can get over thinking our children will end up like the Star Wars kid or that poor Numa Numa Dance fellow. I don't see it happening with the bath video, but maybe with Zoë's "Shake Your Booty" song.

might post if Brooke can get over thinking our children will end up like the Star Wars kid or that poor Numa Numa Dance fellow. I don't see it happening with the bath video, but maybe with Zoë's "Shake Your Booty" song.Also last night we completed season five of 24. I love the series, and season five was great, especially Gregory Itzin and Jean Smart as the president and first lady. I've now seen the whole thing through last season, and haven't a clue what has happened this season. I'm pretty sad to read that Melanie McFarland, the most trusted hairdo in TV reviewing, isn't "feeling it anymore." It will be a while before I can start in on season six. What'll we watch next? Back to Entourage, perhaps, so I can dream of being a movie star.

This morning I got in a good long walk with Yagi. Through the I-90 walking tunnel, down to the lake, and along the water while Yagi swam and carried big sticks. I'm off now for a haircut, then to pick up Zoë. Again, no nap. What the hell is going on here?

It's a nice pace. Next time maybe we'll go for the cottage.

Patient Satisfaction

usually following publication of research or polls. I'm interested in what contributes to satisfaction in the patient-doctor relationship, though I'm not convinced that we need to be satisfied to have our needs met. Or, put another way, offering the best and safest medical care may not always satisfy my patients--or me. There is a lot of research about satisfaction, but no clear evidence that satisfaction matters. It is assumed to be its own valid outcome, though it is hard to measure reliably. There are a couple of fun satisfaction items that have landed in my Google Reader recently.

usually following publication of research or polls. I'm interested in what contributes to satisfaction in the patient-doctor relationship, though I'm not convinced that we need to be satisfied to have our needs met. Or, put another way, offering the best and safest medical care may not always satisfy my patients--or me. There is a lot of research about satisfaction, but no clear evidence that satisfaction matters. It is assumed to be its own valid outcome, though it is hard to measure reliably. There are a couple of fun satisfaction items that have landed in my Google Reader recently.Yesterday I ran into this Annals of Internal Medicine study on management of patient expectations. The investigators audiotaped 200 medical visits and documented what patients wanted, then asked them later how they felt about the visit. It turns out that 97.3% of pre-visit expectations were at least discussed during the visit. How did these expectations come up? Forty percent of the time patients brought up directly ("I would like _______." Good, solid communication). Thirty percent of expectations came out by having patients mention symptoms. Also good communication; it's my job as a doctor to help people make sense of their symptoms. More than a quarter of expectations came out through "physician-initiated discusson." I'm not sure exactly what that means. Would patients never have mentioned these things if the doctor hadn't chased after it? Or did the doc just get there first? Thinking about this would get me way off track, so I'll drop it.

Regardless of how things came up, expectations were met around 67% of the time, and where doctors weren't comfortable, they did the right thing and suggested alternatives only around 22% of the time. I guess the rest of the time they just said: "Uh, no."

And what about satisfaction? "Patient satisfaction and trust remained high, regardless of whether expectations were met." So what can I learn from this study? Should I worry about what patients expect? If expectations aren't related to satisfaction, well then what is? And does satisfaction matter? I know plenty of people who aren't satisfied with their doctors, but they keep going.

And what about satisfaction? "Patient satisfaction and trust remained high, regardless of whether expectations were met." So what can I learn from this study? Should I worry about what patients expect? If expectations aren't related to satisfaction, well then what is? And does satisfaction matter? I know plenty of people who aren't satisfied with their doctors, but they keep going.Item number two showed up in Family Practice Management's March News & Trends, reporting on a Consumer Reports survey. I've pasted the clip in green below with my comments along the way.

The good news for physicians: The overwhelming majority of patients said they were "highly satisfied" with their doctor and that their health improved under their doctors' care. In addition, 77 percent said their doctors treated them with respect and 67 percent said they were patiently listened to and understood.

Already this seems more useful than the Annals piece, as they ask whether patient health actually improved. I'm also happy CR asked about respect, but shocked that so few doctors listen to and respect their patients. CR presents this under the good news header!

The bad news for physicians: The majority of patients said their doctors never talked to them about the cost of treatments and tests.

I hate talking money with patients, and frankly feel ill-equipped to do it. I know tons about tests and treatments, but very little about what they cost. My ePocrates handheld reference gives me some info, but I can't predict what insurance will cover and at what rate. I saw a patient in clinic one day with chest pain. It wasn't his heart, but when I shared with him some chest pain (i.e. heart attack) warning signs that should prompt him to call 911, he began to quiz me on on the costs of ambulance transport and emergency care. I had no idea what to tell him, and felt bad about it. I know money matters, but I just don't have the answers.

In addition, patients had these complaints:

• 74 percent said their physicians had not asked about emotional stress.

• 24 percent said their physicians made them wait 30 minutes or more.

• 19 percent said they couldn't get an appointment within less than a week.

I cannot believe that there are still non-surgeon physicians who don't ask about stress. The second two complaints above are systems issues, and inexcusable. I think making patients wait around to see a doctor demonstrates a real lack of respect for the value of their time. Patients don't have all day to hang out in clinics, waiting to be seen. Also, having to wait a week when you're sick or when your kid is sick and you're worried is just plain wrong. Who wouldn't go to the ER under those circumstances? Same day or next day access isn't that hard to provide; we should be doing it.

I cannot believe that there are still non-surgeon physicians who don't ask about stress. The second two complaints above are systems issues, and inexcusable. I think making patients wait around to see a doctor demonstrates a real lack of respect for the value of their time. Patients don't have all day to hang out in clinics, waiting to be seen. Also, having to wait a week when you're sick or when your kid is sick and you're worried is just plain wrong. Who wouldn't go to the ER under those circumstances? Same day or next day access isn't that hard to provide; we should be doing it.

Sure. But I haven't done my back exercises in months, so I get that it's not always easy to do what you're told, even when you know it will help.

Other physician gripes included the following:

• 41 percent said that patients wait too long before making an appointment.

Or are they just waiting for their appointment?

• 32 percent said patients are too reluctant to talk about their symptoms.

Except emotional stress, which we don't want to talk about.

• 31 percent said patients request unnecessary tests.

Bloody internet.

• 28 percent said patients request unnecessary prescriptions.

Bloody advertising. In this case, I refer back to the Annals paper, which reminds us that it is important to negotiate with patients. We shouldn't offer wasteful or harmful interventions to patients, even if they want them. We should offer alternatives that address patient concerns and hopes.Two more publications on satisfaction, and I still have no good idea about it's value, or even what it really is. I do know there is value in listening and respecting patients, getting them in when they need me and seeing them on time. And I'd like them to feel healthier.

But satisfied?

Sunday, March 11, 2007

Pain on the Brain

Recently, my residency program has been working on how we help patients with pain. Honestly, some of this comes from the great frustration the doctors and staff at our three clinics feel with "pain patients." It feels like patients with chronic pain take up a lot of our time and energy, and we end up not helping them very much--they still have pain. Stuck in our doctor brains is the notion that if something is wrong, we should be able to fix it, or at least help patients fix it. So when things don't get better--the pain is the same or worse--over months of treatment, we get frustrated, and so do our patients.

Recently, my residency program has been working on how we help patients with pain. Honestly, some of this comes from the great frustration the doctors and staff at our three clinics feel with "pain patients." It feels like patients with chronic pain take up a lot of our time and energy, and we end up not helping them very much--they still have pain. Stuck in our doctor brains is the notion that if something is wrong, we should be able to fix it, or at least help patients fix it. So when things don't get better--the pain is the same or worse--over months of treatment, we get frustrated, and so do our patients.One of the most difficult issues revolves around pain medications, specifically narcotics. Treatment of chronic pain with opioids (commonly vicodin, percocet, oxycodone, and methadone in our clinics) has a long history, and opinion about its value and safety seems to swing like a pendulum. In primary care settings, the pendulum has swung into the "avoid narcotics" zone over the last several years. There is a lot of well-founded concern for the long-term safety of narcotics, and for the harm we do to patients by creating dependence on these medications. But that's not what really makes us uncomfortable.

It's a trust thing. Misuse of narcotics--overuse, diversion--is a reality, and doctors are justifiably nervous about the possibility that the potent medications we prescribe might be used to feed addiction or for monetary gain. There's good evidence that this happens, even among patients we believe to be using narcotics appropriately. We can't be sure, and we're not comfortable with a sham therapeutic relationship.

Unfortunately, that anxiety about trust sets up a difficult relationship with patients when they come to us with pain. When I hear a patient report low-back pain, my differential diagnosis always includes inappropriate drug-seeking behavior. There is no other complaint that sets off these kinds of alarms. I find that when this suspicion come up, I might test a patient with a few non-narcotic suggestions, like physical therapy, but these maneuvers only contribute to the discomfort and don't clarify anything. Worse, failure to embrace physical therapy as the best idea ever and suggest, perhaps, a short course of vicodin ("I had some left from a procedure and they seemed to help") puts the patient at risk of being branded as a drug seeker--the pseudo-addict.

All of this has been stuck in my sleepy head recently as I've done this narco-dance with a few new patients and worried a lot about how to wean the few patients of mine who take opiates chronically. The residency pain task force is doing it's thing, and will certainly produce some helpful resources for my patients, but I'm not good at waiting, and the folks I care for have pain now.

A couple of weeks ago I put together a five page "Menu of Treatments for Low-Back Pain" for one of my patients. I had hoped to use some chronic disease management techniques to create a plan with her that would be as transparent as possible. I created the menu from the collected works of the Cochrane Back Group and offered it to her as a way to start us both thinking about how to help her to a tolerable level of pain. The menu concept is popular in managing chronic diseases like diabetes and hypertension that require patients to change behaviors. It gives people options and lets them choose what they think they can do. It is important to build the menu around goals--another chronic care pillar--and so we spent some time discussing what she hoped to accomplish regarding her pain. I thought it went well.

A couple of weeks ago I put together a five page "Menu of Treatments for Low-Back Pain" for one of my patients. I had hoped to use some chronic disease management techniques to create a plan with her that would be as transparent as possible. I created the menu from the collected works of the Cochrane Back Group and offered it to her as a way to start us both thinking about how to help her to a tolerable level of pain. The menu concept is popular in managing chronic diseases like diabetes and hypertension that require patients to change behaviors. It gives people options and lets them choose what they think they can do. It is important to build the menu around goals--another chronic care pillar--and so we spent some time discussing what she hoped to accomplish regarding her pain. I thought it went well.Mind you, in several visits we haven't touched on her hypertension, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia. And I haven't gotten close to talking about preventive care: pap smears, osteoporosis, etc. Missing these things is another hazard of chronic pain.

Okay, so I started this not to whine but to describe a chain of events and some hopeful developments. The back pain menu was a nice little organizing moment for me. There are heaps of options for patients with pain. For any given intervention, the data might not be thrillingly positive, but most of them work for somebody, and in combination, I have to believe that we can find a way to decrease pain.

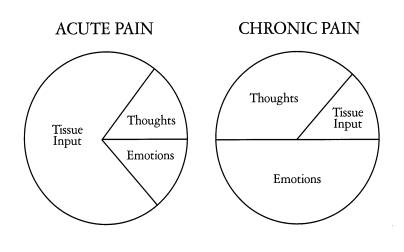

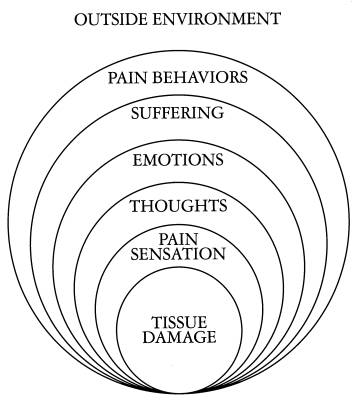

We've also got resources in our own clinics. Like chronic disease management techniques, cognitive behavioral therapy techniques have a place in the management of chronic pain: one's process of thinking-feeling-behaving is vital to one's experience of pain.

As an exercise in organizing these ideas into a practical approach, I'm working on a web-based collection of resources. The Pain Page will catalog evidence-based interventions for pain, local resources, patient perspectives on living with pain, media coverage of related issues, and how our work as physicians and patients relates to regulatory bodies.

I hope this will help my colleagues, patients, and me build together a transparent and effective structure for collaborating on a problem we all would like to handle better.